Definition

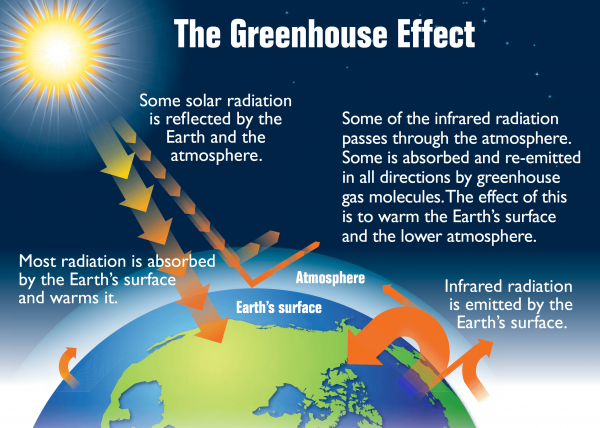

Although the overall percentage of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere may seem small, greenhouse gases have the unique ability to absorb thermal energy, unlike non-greenhouses gases like oxygen and nitrogen. Greenhouse gases act as a layer of insulation around the planet, keeping Earth’s surface at a habitable temperature and allowing life to flourish.

Energy from the sun reaches the Earth through radiation. About 29% of this incoming solar radiation is reflected into space by clouds, atmospheric particles, and large snow and ice surfaces. Of the remaining 71%, some is absorbed by the surface, and some is absorbed by heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, also known as greenhouse gases (GHGs), which includes carbon dioxide, water vapour, methane, and other trace gases. 1

Source: Wikimedia Commons. (2015). Earth’s Greenhouse Effect [Online]. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8e/Earth’s_greenhouse_effect_(US_EPA,_2012).png

Context

Since the early 20th century, so many additional heat-trapping greenhouse gases have been released into the atmosphere that this delicate balance has been disrupted. The primary source of these additional greenhouse gases is carbon stored in fossil fuels, which combines with oxygen to form carbon dioxide when fossil fuels are combusted. Similarly, carbon stored in trees is released in the process of deforestation and land use change.

Normally, the balance of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is in part maintained by natural carbon sinks such as oceans, forests, and wetlands. However, the rate at which greenhouse gases are being added to the atmosphere outstrips the rate at which carbon sinks can absorb carbon. There is also evidence that rapidly warming temperatures and loss of natural ecosystems can reduce the ability of carbon sinks to absorb carbon. 2

Carbon vs. Carbon Dioxide

We often measure carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere in parts per million, which means that for every 1 million molecules of gas, approximately 413 will be carbon dioxide molecules 3. Greenhouse gases are not all evenly distributed throughout the atmosphere – for example, water vapour is highly variable across places and seasons. 4 Each part per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere converts to 2.13 gigatonnes of carbon. 5 Note that this is carbon, not carbon dioxide. When stored carbon enters the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, each kilogram of carbon becomes 3.67 kilograms of carbon dioxide, so each part per million of carbon dioxide converts to 7.81 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide.

Why does this distinction matter? Although carbon and carbon dioxide are often used interchangeably, the distinction has important implications for calculating how much carbon dioxide needs to be removed from the atmosphere, or prevented from being released, in order to stay within a certain carbon budget.

Source: vectorstock.com/24883408

Let’s do a comparison: A carbon pricing policy introduces a price of $50 per tonne of carbon dioxide. If we convert this to the price per tonne of carbon, the carbon price would rise to $30 x 3.67 = $183.5/tonne C. This clarification may impact how high carbon prices are set, or how high emitting industries evaluate their ability to continue operations as usual in an increasingly carbon-constrained world.

Pay close attention to whether it is carbon or carbon dioxide being discussed, particularly in discussions about fuel sources (in which carbon content is an important characteristic), and their resulting carbon emissions (which usually refer to carbon dioxide).

Why do we focus so much on carbon dioxide? What about the other greenhouse gases?

CO2 has contributed more than any other driver to anthropogenic climate change, so it is often at the centre of conversations on emissions reductions and global warming. It is also more abundant than other heat-trapping gases such as methane, so it has an overall larger impact on global warming.

However, other greenhouse gases can have a higher heat-trapping ability than carbon dioxide. Methane in particular is becoming increasingly important, as the widespread use of fossil fuel extraction processes like fracking produce large amounts of methane emissions. Livestock farming and land use change are also leading causes of increased methane emissions in the atmosphere. Other emerging issues, such as the potential melt of permafrost due to global warming, may release even more methane emissions that have remained frozen in ice.

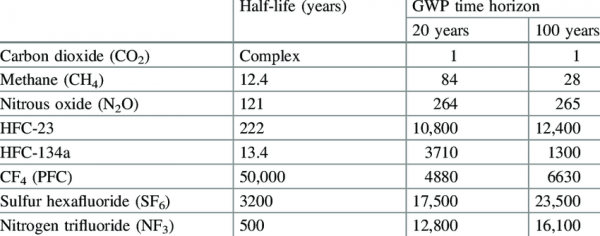

Global warming Potential (GWP) and CO2e

This table 6 shows a comparison of the heat-trapping ability of different greenhouse gases, which are represented using the gases’ Global Warming Potential, or GWP. GWP is a unit to compare gases’ heat trapping potential using carbon dioxide as a baseline (GWP = 1), across different time scales (usually 20 years and 100 years are used in calculations).

This comparison allows emissions of different GHGs to be consolidated into a single measure, often CO2e, or carbon dioxide equivalent.

Whether the 20 year GWP or 100 year GWP are used depends on the circumstance, but one important consideration when it comes to methane is that methane has a significantly higher heat-trapping ability in its first 20 years in the atmosphere. This means that it creates a strong burst of warming over a much shorter period, which could have permanently damaging consequences for natural ecosystems that cannot adapt that quickly, and trigger positive feedback loops. 7

Dive deeper

Recent blog posts about Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Student Energy at the UN Climate Action Summit

September 20, 2019

External resources

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (2009). Earth’s energy budget. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/EnergyBalance/page4.php

- Climate Central (2011). Climate change may make carbon sinks less effective experts say. https://www.climatecentral.org/news/forests-and-oceans-help-store-carbon-but-are-vulnerable-to-climate-change

- Energy Systems Research Laboratories (n.d.). Trends in atmospheric carbon dioxide. https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/

- Center for Science Education (2012). Carbon dioxide 400ppm atmospheric concentration diagrams. https://scied.ucar.edu/carbon-dioxide-400-ppm-diagrams

- Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (n.d.). Conversion tables. https://cdiac.ess-dive.lbl.gov/pns/convert.html#3.

- Soeder, D. J. (2018). Clay: Geologic Formations, Carbon Management, and Industry. In Greenhouse Gases and Clay Minerals (pp. 33-54). Springer, Cham.

- Myhre, G., D. Shindell, F.-M. Bréon, W. Collins, J. Fuglestvedt, J. Huang, D. Koch, J.-F. Lamarque, D. Lee, B. Mendoza, T. Nakajima, A. Robock, G. Stephens, T. Takemura and H. Zhang, 2013: Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WG1AR5_Chapter08_FINAL.pdf