Yukon Exploration with The Howl Experience

Our Fellowship Coordinator Ryan Sojnocki recounts his time in the Yukon Territory learning about climate change and Indigenous Ways of Knowing with the Howl Experience experiential learning travel group!

Last September 2023, I had the transformational experience of participating in a week-long Howl program based in the Yukon. ‘Howl’ is an organization based out of Canmore, Alberta that provides young people between the ages of 17-30 with experiential learning opportunities rooted in community building, climate change, reconciliation, and personal resilience. The organization offers several programs across Canada, including programs running in Canmore, the Yukon, and the Maritimes. To participate in one of these programs, participants are asked to pay what they can to help support the cost, but most of the expense is heavily subsidized to make it accessible to young individuals and youth from marginalized or disadvantaged backgrounds.

-

The view from the Kluane Lake Research Station kitchen

-

Ryan’s Howl group joined around a campfire.

For my experience, I participated in their “Yukon Exploration” program which was mostly centered at the Kluane Lake Research Station located just outside of Kluane National Park. To argue that spending five days at a research station set amidst one of the most serene landscapes I’ve ever seen was merely transformational, does not capture the full magnitude of this experience. Kluane National Park houses the largest nonpolar icefields in the world and acts as a global hub for researchers exploring topics connected to climate change, sustainability, reconciliation, and conservation to name a portion of the prevalent issues studied at the station. During our time at the research station we had the chance to learn directly from climate science researchers, hear from Parks Canada conservation and management staff, spend time with local Indigenous communities, and hike throughout the park. From my perspective, the goal of this experience was to expose youth participants to the interconnectedness of social and ecological problems our world faces, and to help build a foundation for change based on traditional Indigenous Ways of Knowing and scientific research methodology. My trip’s educational programming was, of course, combined with breathtakingly bright night skies, campfires, group bonding activities, and daily cold plunges in the frigid glacier-filled lake.

When I look to unravel this experience, a few core takeaways stand out to me. Shortly after we arrived at the research station, instructors told us about the Grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) in the area, informed us that we were expected to bring bear spray with us at all times, and to always let someone know where we were going. This protocol was met with a noticeable level of anxiety from the group, as many of us had spent most of our lives living in areas where the local predator population had been eradicated. It wasn’t until we spent time with local Indigenous Elders that my perspective surrounding bears–or humans’ interconnection to the natural world more broadly–was forever changed.

-

Wilderness right outside of Ryan’s bunk

-

A spoon carved from a moose antler

-

Ryan’s hand next to a Grizzly paw print in the sand.

Wilderness right outside of Ryan’s bunk, a spoon carved from a moose antler, Ryan’s hand placed next to a Grizzly paw print in the sand.

Through conversations with the Indigenous Elders, I became aware of how disconnected I have been from a vibrant and intact ecosystem, and the feeling of humility and awareness that comes from it. Growing up I played in forests filled with deer, raccoons, coyotes, and squirrels thinking that was normal. What escaped me was that during my grandfather’s childhood he would play in those same forests, where then there were moose, wolves, and bears that he could have encountered.

I feel personally fortunate to have gotten to learn from Indigenous Elders who share ancestors with those who have spent thousands of years coexisting with the animals around them, while granting them the respect, awareness, and protection they deserve. My experience leaves me wanting to help shape communities towards a healthier connection with the natural world. Humanity exists inseparably within nature; our species is not above nor separate from it. We are meant to walk alongside the natural world rather than trample through it.

-

Structures on James Allen’s trapline

-

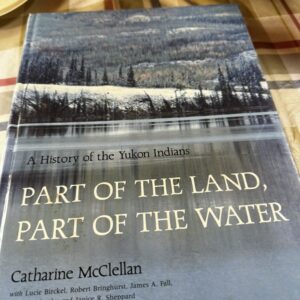

Some of Ryan’s reading material that paired well with his trip

I was also quite shocked to see the landscape-altering effects of a glacier that no longer feeds into Kluane Lake, and wondered what was happening to this pristine watershed. Being on the outskirts of the largest nonpolar ice deposit in the world has a way of inspiring conversations about the impacts of climate change by default, but Kluane Lake is Yukon’s largest lake and the glacier that was its main feed source is now being diverted to Alaska. Each day as I would gaze across the lake I could see the sediment blow around, left over from the dried-up riverbed, leaving me to wonder what would happen to the watershed if the glacier didn’t divert back. Although this change carries a negative connotation for many who have observed the phenomenon, we received a glimmer of hope from James Allen, former Chief of the Champaign & Aishihik people. When we were visiting the ‘Shakat Tun Wilderness Camp’, a trapline owned by the Allen family for countless generations, James told us the story of the same thing happening 400 years ago and reminded us to always have humility when it came to our relationship with Mother Earth. This experience connected me to the pulse of an ancient landscape and taught me how my preconceived ideas of what is ‘normal’ or ‘natural’ in an area is often restricted by the shallow understanding afforded by the relative shortness of my own life. I was grateful to learn from James and his family, and be reminded to always seek Indigenous knowledge when addressing environmental and social issues affecting a region and population.

Participating in Howl and having the opportunity to travel to the Yukon- a place at the forefront of social and environmental research, rich in Indigenous culture, and full of serene landscapes- deeply transformed my personal and professional life. When we were in Whitehorse, we visited the Yukon University and heard from the Climate, Conservation, and Energy Research Labs on the incredible projects they are working on. Combined with my experience at the Kluane Lake Research Station, my conversation with Paul McCarney, a Research Professional for the Northern Systems Conservation Co-Lab and Natural Resources Director for the Vuntut Gwitchin Government, inspired me to pursue a master’s and build a career working with remote communities in Northern Canada to help address some of the social and environmental these regions are experiencing. Over the coming months, Paul’s support has transformed my personal and professional goals and has opened my eyes to the intersections of social science, natural science, and local and Traditional Knowledge. For everything he has done and continues to do for me, I owe him a world of thanks.

Canada’s youthful generations have some monumental problems to address, and I believe that it is only through a deep respect for the interconnectedness of humans and our home that we can begin to solve them. Fortunately, Indigenous communities across the world are leaders in this space and through reconciliation, humility, and awareness, I believe we are well on our way!

Ryan Sojnocki has been a Fellowship Program Coordinator at Student Energy for over two years. Before joining the organization, he helped coach and mentor early-stage social ventures at the University of Waterloo, and has carried that passion into his role working with youth around the world to help build successful energy projects in their targeted region. When he’s not working, you can often find Ryan immersed in the backcountry of British Columbia or deep in a philosophical conversation about the many intricacies of being human.